The readers’ poll in tonight’s edition of thelondonpaper asks whether Led Zeppelin were the greatest band ever.

The question has sent me scurrying back through the depths of my ipod, listening to their songs with an attention I haven’t paid since high school.

I tend to think questions and polls about the best band/ album/ song are a bit of a waste of time. All they do is encourage people to attempt the impossible - constructing logical scaffolding around their (emotionally based) tastes. It’s seldom a seemly sight. (Besides the answer is clearly Belle and Sebastian/ Her Majesty (The Decemberists)/ I’ve been loving you too long (Otis Redding). And I can prove it with algebra.)

But Led Zeppelin thing has a certain weight to it (pardon the pun). Because, questions of how good they were as a band aside, they were a spectacularly consistent brand.

And what did the brand stand for? Power.

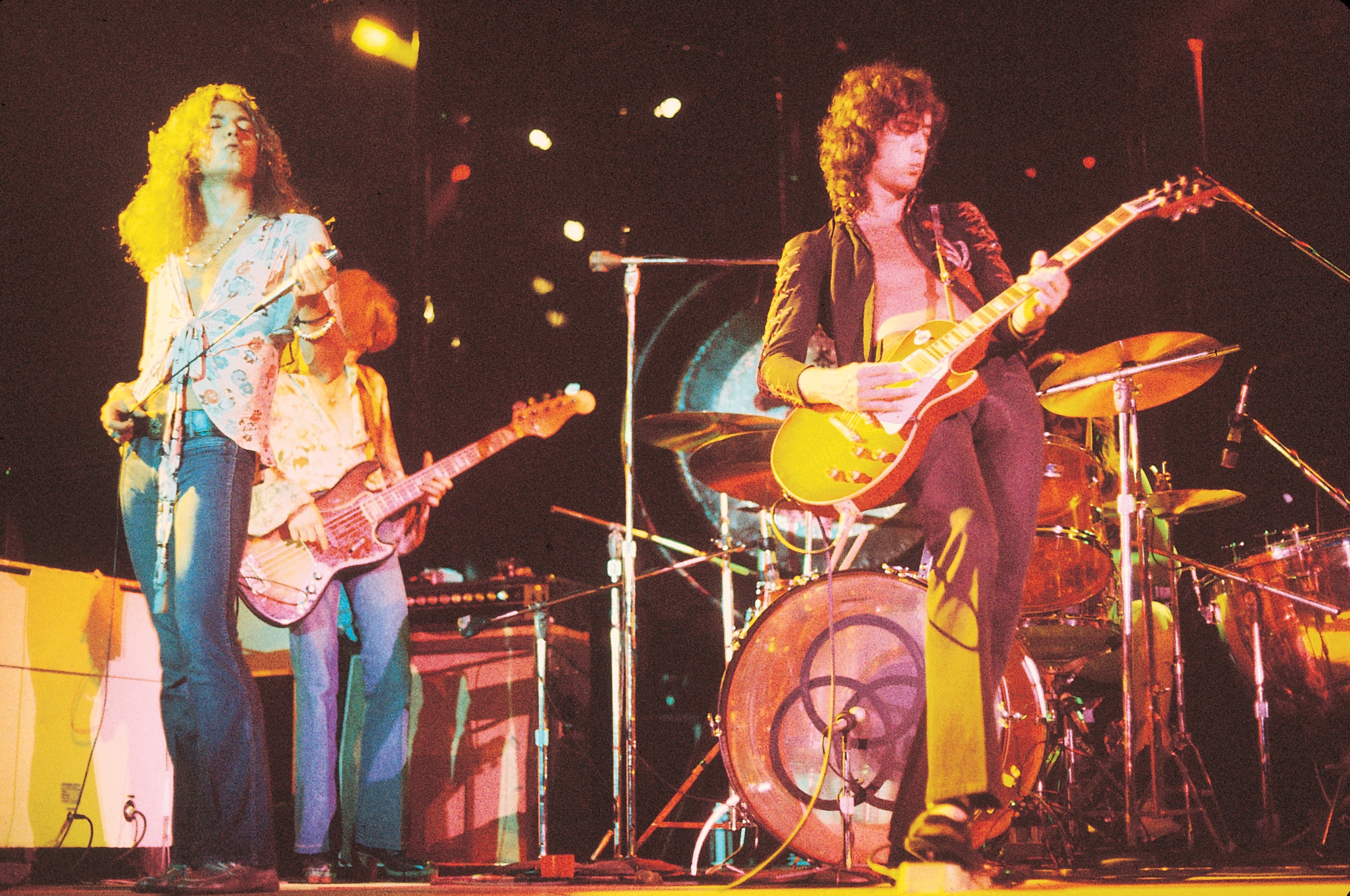

Virtually every component of their music was some kind of dominance display. The force with which John Bonham hit the drums (so loud, apparently, that they often used to set up the mics in the next room when recording to avoid redlining the meter). The range and power of Robert Plant’s vocals. The lightning speed of Jimmy Page’s guitar playing. The Terminator-like precision of John Paul Jones’s basslines. And of course the sheer volume of their live shows.

It’s difficult to think of another band that hewed so single-mindedly to an aesthetic, from Plant’s tight pants to the Norse god imagery that became their leitmotif.

Even their quieter moments, you get the feeling, were only there to make the loud bits seem more powerful. (And of course to casually show off their virtuosity in that area too).

Sure, there have been louder, faster and heavier bands since. Possibly there have even been more technically adept ones.

But most of those sacrifice some elements for the benefit of others – the boring, root-note bassline that serves to anchor the guitar; the unimaginative melody that simply echoes the killer riff.

At risk of reducing art entirely to commerce, I wonder how much of their success stemmed from staking out a compelling proposition and executing it brilliantly?